11/17/2021 The Every Ridge Project

By Beth Lopez - Trail Runner, Skier, and Snack Enthusiast

Socks covered with spiky burrs, faces crusted with sweat, dirt-dusted scabs streaking every limb, tree sap clumping our hair, we plopped onto a rare patch of grass on the Wildcat Ridge and sipped some of our last ounces of water. I intently studied the haphazard compilation of beta I’d saved on my phone, keen to get to the Neff’s Canyon spring before the triple-digit heat got the best of us.

“This is awesome,” said Eli.

He wasn’t wrong.

We were, in fact, achieving my goal of the summer, one route-finding chunk at a time.

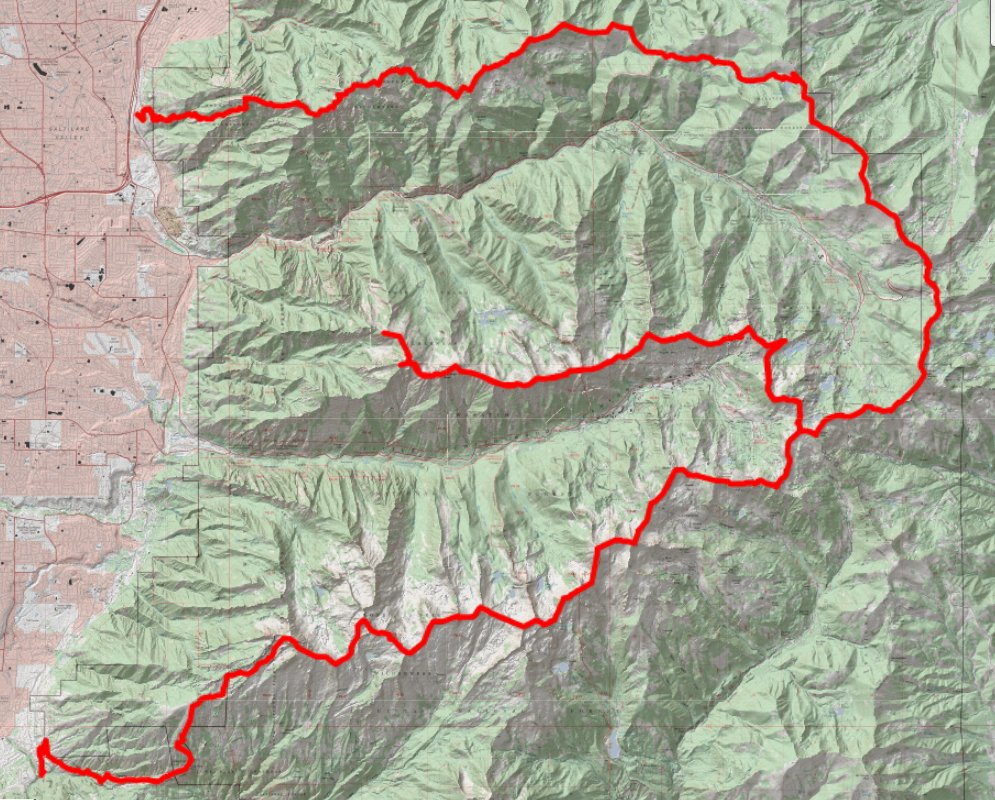

Excluding sections I’d already done, I wanted to scramble the main ridgelines that connect Lone Peak to Mt. Olympus, as well as the Cottonwood ridgeline from Brighton to Broads Fork Twin Peaks. And here we were, experiencing the Type Two joy trail-hikers might never taste.

I’d spent every summer of my life running around the Wasatch, attracted to its picturesque peaks as they made the most wonderfully goatly sitting spots. Then, during the summer of 2020, I was benched, rehabbing an exploded knee, fresh out of surgery. Hiking and running were out, and I soon realized how much mountain sports propped up the house of cards that was my mental health. Throw in a pandemic that took away socialization—my other mental salve—plus a good dose of global instability, and I was in the lowest place I’d ever been.

The only thing that helped at my low point was plotting future high points. I positioned my computer on the handlebars of my spin bike, combing over the contours of the Wasatch on Google Earth to plan next winter’s hoped-for ski lines. But what I really noticed was how much terrain I’d never touched on the Wasatch’s ridgelines.

The jagged, remote, tough-as-a-bugger-to-get-to ridges connected the peaks I’d worshipped my whole life, and I started to realize how intriguing all the in-between places were. And how challenging they’d be to cover, remote and jagged as they were. I wanted to try the WURL eventually, and it’s still on the list, but that route felt like only part of the puzzle. I decided to go beyond any established linkup routes and, instead, set the goal of spending summer 2021 covering the ridges encircling the Cottonwoods.

“It’ll be my ode to the Wasatch!” I declared. “A love letter to all the places in between!” It would be a communion with the mountains, testing out my new knee-joint infrastructure on terrain that was feral, free of trails, and low on beta.

Fast-forward to this summer, with battle-hardened knees. My fog of depression lifted now that I knew it was possible to come out of an injury stronger. The injury was just a chapter of the hero(ine)’s journey …

Which took me to the one blessed grass patch on Wildcat, from which my good friends Eli, Melinda, and I managed to choose the least navigable side of the knife-edge between Wildcat Ridge Peak and Peak 9755. Grasping at tree roots and loose choss chunks that tumbled into Neff’s Canyon below, we finally made it to the meadow descending to Neff’s Spring. We’d done it. It only took 12 hours, minor sacrifices of blood, and a lot of trial and error in route finding, but we’d done it. The first section of my summer ridge project was checked off.

From there, every weekend had a big day dedicated to the project. I cataloged and completed everything I hadn’t navigated before. Bonkers to Twin Peaks. Twin Peaks to Sunrise to Dromedary. Honeycomb Ridge to Flagstaff. The Sundial to Mt Superior. The Beatout from Pfeifferhorn to South Thunder. The White Baldy ridge. The funky steep glades from South Thayne Peak to Mt Raymond.

Some sections took multiple attempts—it was easy to underestimate the time it could take to cover new ground. But since my goal was more laden with excitement than fussiness, I never minded coming up short and coming back to try again.

A crew of fellow masochists rotated through to accompany me, with my friends Eli, Melinda, and Eric, plus my husband Sean joining up for various sections. Every mile we covered was valuable research, so if we didn’t finish everything we wanted to in a given day, it was just an excuse to come back and pick up where we left off, newly armed with more knowledge.

Every day netted out positive, but there were a couple of sweaty-palmed moments that I ruminated on long and hard afterward. Like getting off-route on the cliffy notch between Sunrise and Dromedary, perched on a sloping ledge that had just enough loose dirt on it to make my next step feel utterly insecure. Tanner’s Gulch yawned open for 3,000 feet below, and if I blew my next move, I’d tumble all the way to the Oktoberfest parking lot. Pissed at myself, I exhaled, found a handhold of unremarkable quality, and tiptoed to safety.

Home in bed that night, I thought about all the tragic search and rescue reports of the summer. I hated feeling like I’d done something sketchy and gotten away with it just by luck, while clearly, not everyone else experienced the same luck. Eventually, I processed the feeling and decided that doubting myself wouldn’t make me better at moving in the mountains, but learning lessons from dubious moments would. I’d had plenty of dubious moments over the years, and the more I learned from them, the less I’d repeat them.

And, there were many more moments of sheer awe. The undulating checkerboard of granite ledges on the south side of Lightning Ridge felt like a twisty playground. The maze of massive granite blocks comprising White Baldy, with crack systems and rock seams all suggesting they might be the way to the summit. The foreboding theatre of Monte Cristo cirque, shadowy as Mordor and even scarier because it’s real.

My body felt more giddy than tired at the end of each day, and my rehabbed knee didn’t grumble much—especially once I treated it to fancy pink carbon trekking poles. I’d long resisted trekking poles, but this chapter of my life was teaching me how it’s so much more valuable to cover distances than to feel cool.

In fact, countless lessons and reminders arose from the project: Bell’s Canyon takes forever to get down. Broads Fork somehow takes more forever-er. Always take the chance to top off water at streams and lakes. Eat a billion calories, and since those calories are expensive in the form of energy bars, learn to make bars at home. Don’t go up things you don’t have a way to retreat off of. Car beers taste good even when warm. Hades is real, and it’s found on the southwest face of Triangle Peak.

The last day of the project was a re-try of White Baldy peak ridge. I’d gotten to the top from the west a few weeks before, but it had taken longer than planned to route-find up, so instead of completing the circuit to Red Baldy, we called it a day. Now, giddy with the knowledge that White Baldy to Red Baldy was the last section of the whole shebang, I felt calm and happy as I inch-wormed up a dubious crack system that definitely wasn’t the way—but it was a way. Sure enough, we reached the summit, now completing the last puzzle piece of the route I’d been exploring sections of since high school.

Completing the final piece gave me the satisfaction of having worshipped my beloved Wasatch in whole new ways. I came into the project thinking I knew the range well, and wrapped the project realizing there’s so much more to get to know. The moonlike upper reaches of Hogum, the gnarly ridges bounding Cardiff’s, the dark cathedral of Stairs Gulch. All the places where the Wasatch holds its cards a little closer to its chest.

While I felt nostalgic about the project the moment I wrapped it, the vacuum was instantly filled with excitement to ski all the lines I’d spotted during every head-scratching moment of route finding. Scrambling these things was fun enough. But with skis, I’ll get to soar on them.